Steve investigates a little-known insect that's probably more important to trout fishing than we realise.

It was a pre-Xmas fishing trip in 2010. As the last of the evening light dissolved into a black but mild summer night, I strained to watch several moths that fluttered in the gentle starlit ripple. I stared with the kind of concentration that comes from the hope a decent-sized brown trout might start mopping them up.

There were no moths in the air and none of the ‘plops’ you might expect if they had crash-landed onto the lake. (Think the great Bogong moth plague of 2007.) As I was wondering where all these moths were coming from, I had an epiphany! So, I watched more carefully. The moths were just materialising. One minute, there was no moth, and then there was a flutter and a bit of commotion on the surface. Then, they just flew off.

I looked at one by torchlight as it fluttered by on the surface. If ever there was a moth you would call ordinary-looking, this was it. Small to medium-sized, beige, and nowhere near as scary as some of the aerial beasts I’ve encountered on the lake whilst using a head torch to fix a tangled tippet. In fact, they didn’t seem at all interested in my torch. As a Conan Doyle fan, I summoned some Sherlock Holmes’ wisdom: “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” Bloody hell, I thought as I leapt to the conclusion these moths must be coming from under the water and then taking flight! A kind of moth-superhero equivalent of Aquaman! Some research would definitely be required the next day when I had access to books and the internet.

Looking for aquatic moths at Lake Eucumbene.

Looking for aquatic moths at Lake Eucumbene.Of course, the next day turned into the next week and then the next month, but in the meantime, I raised the topic with several other flyfishers, some of whom were interested; others who just looked at me askance. Maybe I was wrong, and as time marched on I began doubting the certainty of my observations.

My interest was reawakened one warm late summer evening later that season when fishing the eastern shore of Lake Eucumbene’s Grace Lea Island. I hadn’t had the new boat for very long and went for an after-charter evening fish on my own. I was wading close to shore, the shallow shale shoreline shelved off quickly into deeper water, and there were literally dozens of these moths popping up and swimming shoreward within a few metres of where I stood. There was no doubt they were coming from under the water! And, as an added bonus, there appeared to be several trout a short way off the bank, intermittently sucking them off the surface.

I tied on the largest, hairiest fly I could find in my box, a Dishington’s Deer Hair, donated some time ago as ‘a good moth fly’ by Col Sinclair, highly buoyant and unsinkable. But after covering a number of fish with quality casts over the course of an hour, I still hadn’t connected with one and was thinking about calling it a day (definitely more research tomorrow). I walked backwards towards the shore, slowly retrieving line onto the reel and starting the lift to pick up the leader and fly. Then, with no more than a few feet of fly-line out the top of the rod (I could have almost touched the fly!) there was this mighty eruption as a monster trout chased the fly off the water, missed it, crashed back into the water, and was gone - leaving me wet and momentarily stunned.

This was to become one of those missed fish adrenalin-packed night terror moments I’ve relived ever since. Years later, I am convinced I wasn’t connecting with those earlier fish that night because they actually wanted that big dry to be moving.

The research

It didn’t take long to find plenty of material relating to aquatic moths. In fact, it’s quite bizarre that I hadn’t come across them before, given there are thousands of species of aquatic moths described worldwide. Locally, the numbers are a little more manageable and in the latest revision of 'Moths of Australia[1],' 54 species are recognised.

I am taking a bit of a punt here, but it is likely that, at Lake Eucumbene, we’re encountering Hygraula nitens, the pond moth, or Australian water moth. But even if it isn’t that exact species, the rest of this story still applies. Aquatic moths mostly have a similar biology and lifecycle. The classification, by the way, goes: Domain: Eukaryota. Kingdom: Animalia. Phylum: Arthropoda. Class: Insecta. Order: Lepidoptera. Family: Crambidae. Genus: Hygraula.

Aquatic moth at Buckenderra, December 2024.

Aquatic moth at Buckenderra, December 2024.Our moth is a herbivore, eating mainly plants, algae and diatoms at various stages of their life. Often, the adults feed on nectar and are important pollinators – while noting that some species have a short life, taking on their flying moth ‘form’ only to breed, and may not feed at all. The larvae (caterpillars) can be found in lakes and rivers and are benthic bottom feeders around rocks and vegetation. They can build cases from the silk thread they produce to bind vegetation into portable homes; a bit like caddis.

The moth goes through four lifecycle stages from egg, to larva, to pupa, and finally, adult. The adults swim down, deposit their eggs underwater on rocks, and then die. In the right conditions, eggs will hatch in one to two weeks, although they will overwinter if laid in late autumn.

Larvae will go through several (five to seven) stages of development called ‘instars’ and again, some may hibernate, or at least not progress, over winter. The pupa (chrysalis) lives underwater, often under a rock, in a cocoon made of silk and leaves, before emerging after around a month, the adult chewing a hole in the cocoon before swimming to the surface. Both the larvae and adult have gills to breathe underwater.

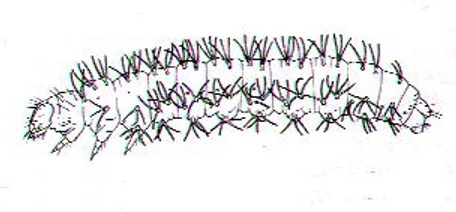

Larvae. (Drawing courtesy of Ian Common, 'Moths of Australia'.)

Larvae. (Drawing courtesy of Ian Common, 'Moths of Australia'.)The literature suggests the adult swims to shore to dry its wings before taking flight. However, I have without any doubt seen them pop up and almost immediately take flight. Maybe that’s just to get ashore, but they definitely take flight. As touched on earlier, some species may go on to feed as adult moths, but either way, they breed and then die after mating or egg-laying. The adult phase may last from a day or two to several weeks.

Summer 2025

The period December 2024 through January 2025, was a spectacular time for surface bugs on Lake Eucumbene. While the midge and caddis hatches were sporadic, the evening (and dawn) moth activity no doubt went on to support the superb daytime action continued by hoppers, cicadas, and beetles. This was not only because actual aquatic moths – either unsuccessful emergers or late egg-layers – sometimes lingered well into the morning. We also had the feeling that the moths helped get even the best browns in the ‘mood’ to look for big food on the surface in broad daylight.

Anyway, the resultant action was high visibility daytime fishing. Big flies, big fish, lots of takes, lots of inquiries as trout sat under the fly before sometimes sucking it down, or sometimes swimming away. Plenty of polaroided fish that always seemed keen to at least swim over to the plop for a look.

Friend David with an early afternoon surface feeder from Wainui. The moths may have initially helped get fish like this looking up.

Friend David with an early afternoon surface feeder from Wainui. The moths may have initially helped get fish like this looking up.When trout are looking up for a big terrestrial feed, they are rarely too concerned about precisely what’s being presented. My favourite was the PMX (Parachute Madam X). This fly was a clear stand out for me, and others I fished with. I know the best fly is often a self-fulfilling prophecy if you don’t change it, but I have an acutely-developed sense of exactly what constitutes good action on a given day. I saw a lot of people with a grin on their face after they’d been put onto the PMX, such as my French fishing friend David who cleaned up six good browns walking 300 metres on a shallow bank at Wainui Bay in under an hour, in full sunlight, right after lunch. A PB for him.

The main event

As for the main low light aquatic moth fishing itself? The moths produced spectacular surface activity at times as they emerged and/or laid eggs in bursts once the sun had really set. There was a general trend for the moth activity to increase as it got darker, and then eventually subside about an hour after true dark. It’s possible there was a resurgence late at night, but if so, we weren’t around to see it.

Eucumbene aquatic moth feeder on a small black Woolly Bugger, quickly cast ahead of the rise, then pulled smoothly.

Eucumbene aquatic moth feeder on a small black Woolly Bugger, quickly cast ahead of the rise, then pulled smoothly.What seems at least as likely, is a predawn emergence – as touched on earlier. That would explain the lingering moths on the water once the sun had come up.

A couple of other interesting points. The cool, damp easterly ‘sea breeze’ which can be a curse for evening fishers at Lake Eucumbene, thankfully didn’t stop the aquatic moths. And although we generally aren’t fans of full moonlight, the moth action continued under a full moon.

As for the catching during the actual low light emergence and/ or egg-laying, surprisingly, it wasn’t always easy! In line with my Grace Lea story at the beginning of this piece, moving the fly seems an important component. We caught moth feeders moving a large (size 10) Claret Dabbler; a large, leggy black foam fly, and a small black Woolly Bugger retrieved subsurface to suggest (we hoped!) an emerging moth pupa. However, given the number of moth-feeding trout covered, and the ferocity of many of the rises to the naturals, I would have to describe our success rate as only fair.

Moth feeder on a large Claret Dabbler, Middlingbank.

Moth feeder on a large Claret Dabbler, Middlingbank.There’s more work to do here. I suspect if it wasn’t for the high quality ‘moth legacy’ fishing during the day this summer, we would have worked harder at this. What’s that about necessity being the mother of invention?

Aquatic moth lifecycle stages (clockwise): egg, caterpiĺlar, cased caterpillar, chrysalis.

Aquatic moth lifecycle stages (clockwise): egg, caterpiĺlar, cased caterpillar, chrysalis. (Images courtesy of Murray Darling Freshwater Research Centre, Centre for Freshwater Ecology, Identification and Ecology of Australian Freshwater Invertebrates.)

FLYSTREAM FACTS: The Bogong Moth

It would be remiss of me not to raise the issue of the worrying fall in bogong moth numbers. It is no coincidence perhaps that more and more flyfishers have started talking about the aquatic moth at the same time as the population of bogong moths has declined. Land clearing and drought appear to be the main culprits according to this article in the Guardian.

Whatever the reason, in years past, it was always going to be easy for a few aquatic moths to get lost amongst the sheer numbers of bogongs we could at times see on the lake during the warmer months.

Recent and somewhat positive news is, bogong moth numbers seem to have improved since that 2021 rock-bottom, although there hasn’t been another formal assessment of the population. Flyfishers can help the bogong moth knowledge base, by sharing any sightings via this app. Moth Tracker | Mountain Pygmy-possums and Bogong Moths | Zoos Victoria

[1] Moths of Australia, Common, Ian F.B., 535 pp, Melbourne University Press, 1990.